Humanity went from lacking active flight technology to walking on the moon in less than 70 years. The evolution from the first simple computer to a portable device that provides instant access to almost all of human knowledge took just a little more than a century.

Based on that technological trajectory, there is a persistent assumption that our technological capacities are unbounded. Now we’ve turned our eyes to space.

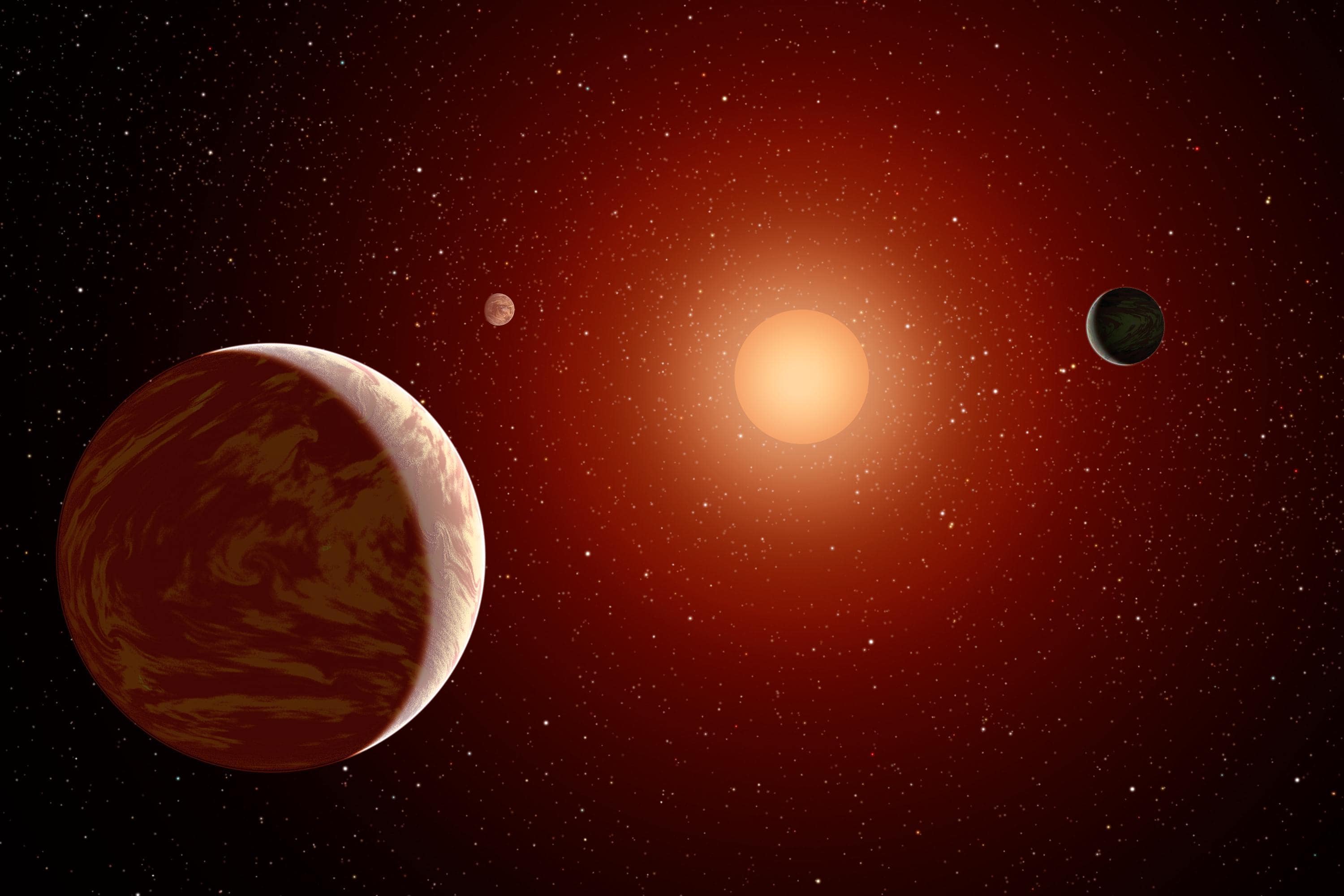

Today, many astronomers no longer ask whether there is life elsewhere in the Universe. We only wonder, when will we find it? Some of the TRAPPIST-1 planets might prove the accuracy of this new study and may be close to finding an answer to this question we have been wondering about.

Despite being smaller and colder than our Sun, the most prevalent stars in the universe can exhibit far more violent activity and intense UV radiation. These M-dwarf stars have a lot of rocky worlds around them, but because of their temperamental nature, scientists have questioned whether or not they are suitable for life. According to a recent study, these worlds might be able to maintain an atmosphere if they undergo a specific evolutionary path.

The research team modeled planets from their molten beginnings to the development of an atmosphere and a rocky crust. According to the simulations, the star probably destroys the first atmosphere that forms, but a second one might form and the planets might be able to retain it.

“One of the most intriguing questions right now in exoplanet astronomy is: Can rocky planets orbiting M-dwarf stars maintain atmospheres that could support life?” lead author assistant professor Joshua Krissansen-Totton, from the University of Washinton, said in a statement. “Our findings give reason to expect that some of these planets do have atmospheres, which significantly enhances the chances that these common planetary systems could support life.”

It is believed that planets should be able to quickly form water in their atmospheres as long as they are in the habitable zone and not too close to the star. The star would initially blow away the hydrogen that covered the molten planet, but on planets with a moderate temperature, hydrogen would mix with oxygen to form water.

Water and other heavier gases would then form an atmosphere that the simulations showed to be stable over time. These cooler planets, where rain forms quickly, have a more stable atmosphere.

The seven planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system are perfect examples of rocky worlds around an M-dwarf. JWST is currently studying them, but so far only data on the closest worlds have been published – and, as expected, they are unlikely to have an atmosphere.

“It’s easier for the JWST to observe hotter planets closest to the star because they emit more thermal radiation, which isn’t as affected by the interference from the star. For those planets we have a fairly unambiguous answer: They don’t have a thick atmosphere,” Krissansen-Totton said.

“For me, this result is interesting because it suggests that the more temperate planets may have atmospheres and ought to be carefully scrutinized with telescopes, especially given their habitability potential.”

The Journal Nature Communications

Cover Image Credit: NASA